What You Missed In The 2019 State-Of-The-City Speech

“The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie…but the myth, persistent, persuasive and unrealistic.”

—John F. Kennedy

Mayor Matt LaVere filled his 2019 State-of-the-City address with images of a utopian Ventura. Unfortunately, it lacked specifics on addressing Ventura’s most pressing issues.

The mayor laid out his seven goals for 2019-2020. His vision included several goals that his predecessors didn’t achieve. Six of the seven were unmeasurable. What’s more, many goals are mere rhetoric and very little substance.

VENTURA’S HOMELESS CENTER

Topping the mayor’s list of priorities was opening a permanent, full-service homeless shelter by December 31, 2019. The date gives this goal specificity. Opening the center doesn’t begin to solve the problem, though. Mayor LaVere and the City Council equate opening a homeless center with improving Ventura’s homeless situation. They are not the same thing.

Topping the mayor’s list of priorities was opening a permanent, full-service homeless shelter by December 31, 2019. The date gives this goal specificity. Opening the center doesn’t begin to solve the problem, though. Mayor LaVere and the City Council equate opening a homeless center with improving Ventura’s homeless situation. They are not the same thing.

Homelessness has risen the past three years to 555 persons from 300 in 2016. In that time, the city has increased spending on the homeless. The problem continues to grow despite spending more tax money to solve it.

The Council and city government are hoping the new homeless shelter will stem the tide. A closer look at the facts, though, shows their hope is not well-founded. There will be 55 beds, and it will cost Ventura $712,000 per year. Filling every bed will still leave 500 homeless persons on the street. The shelter will serve only10% of the homeless population.

What’s more, the City Council conflates opening the center with helping the homeless. The goal shouldn’t be to have beds available. That’s an intermediary step. The goal should be to get the homeless off the street and return them to a healthy way of life.

What’s more, the City Council conflates opening the center with helping the homeless. The goal shouldn’t be to have beds available. That’s an intermediary step. The goal should be to get the homeless off the street and return them to a healthy way of life.

The real solutions to homelessness—a very complex problem—was missing from Mayor LaVere’s vision. There are examples of successful programs in other cities. Looking at successful programs, like the one in Providence, Rhode Island, would be a step in the right direction.

UPDATE THE GENERAL PLAN

The second goal was to reinitiate the General Plan update. Ventura city government will conduct public outreach throughout 2019. Other than holding several long-overdue citizen input meetings, the outcome will be unmeasurable.

The city must try new, innovative ways to reach citizens. Otherwise, it will miss valuable input. Young people are most likely to be underrepresented. Our younger citizens are generally absent from public meetings. Yet they will live with the consequences of the General Plan.

The mayor and City Council are relying upon the voters to be content that the city was doing the outreach.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The third goal is to create a comprehensive economic development strategy. The strategy would include several key focus areas, including:

- Auto Center and Focus Area 1

- The Johnson Drive corridor. Mayor LaVere cited the North Bank Apartment project as an example.

- Front Street. The mayor wants to turn it into Ventura’s version of Santa Barbara’s Funk Zone.

Missing from the address is the vital fact that economic development begins with other people’s money. It takes investors willing to put up the capital to improve the business environment. How will the City of Ventura invite and welcome investors who want to start or move their business in Ventura?

Santa Barbara’s Funk Zone succeeds because the city made it easier to rebuild in the area. Developers lament that Ventura’s city government makes it difficult to do business. Stifling regulations, fees and planning delays force investors to look elsewhere. The new economic development plan should have one single goal to stimulate growth. Force the city to review, streamline or remove building codes and regulations wherever possible.

VENTURA BEAUTIFUL

Mayor LaVere’s fourth goal is to beautify the community. He wants to end what he termed “blight.”

Mayor LaVere’s fourth goal is to beautify the community. He wants to end what he termed “blight.”

Like the economic plan goal in the 2019 State-of-the-City address, this goal relies on “other people’s money.” Homeowners must invest in eliminating the so-called blight. There is no compelling reason for property owners to reinvest in some properties. The same stifling regulations and fees that deter investors hurt homeowners, too.

Following the Thomas Fire, the city reduced the building permits and fees for rebuilding. If the mayor is serious about improving blight, offer similar reductions to anyone enhancing their property. That would be measurable.

COASTAL AREA STRATEGIC PLAN

The fifth 2019 State-of-the-City goal is also unmeasurable and unspecific. Mayor LaVere says we must develop a Coastal Area Strategic Plan. He contends we need this because of climate change. He offered no further details.

The same faults of gaining input for the General Plan apply to the Coastal Area Strategic Plan. Find ways to reach all citizens.

BUILDING COMMUNITY

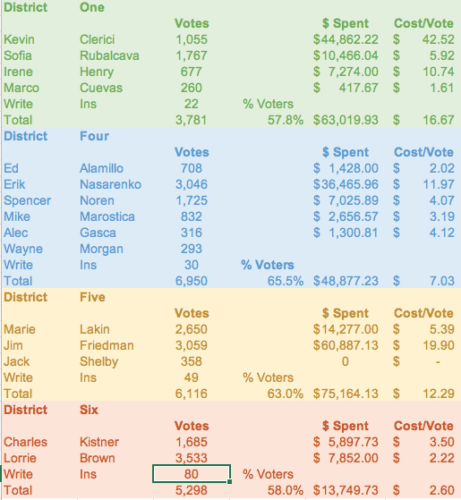

Mayor LaVere’s sixth goal is for the Ventura community to come together by building parks. Building community was a goal of both Mayor Erik Nasarenko and Mayor Neal Andrews. Three years and three administrations later, this goal remains.

The mayor hopes to achieve this goal by building community parks. The Westside Community Park set the model. Mayor LaVere’s first target is Mission Park.

The mayor hopes to achieve this goal by building community parks. The Westside Community Park set the model. Mayor LaVere’s first target is Mission Park.

Like the other goals, rebuilding Mission Park lacked specifics, budgets, timelines or measurable results. Moreover, this plan has one fault the others don’t have, public safety.

Mission Park is home to a growing number of Ventura’s homeless population. To prepare the area, the homeless must move elsewhere. The 55-bed homeless shelter isn’t the solution. Also, even if we scatter the homeless, there are safety issues. Someone would have to clean the discarded needles, drug paraphernalia and human waste from the park.

Mission Park is home to a growing number of Ventura’s homeless population. To prepare the area, the homeless must move elsewhere. The 55-bed homeless shelter isn’t the solution. Also, even if we scatter the homeless, there are safety issues. Someone would have to clean the discarded needles, drug paraphernalia and human waste from the park.

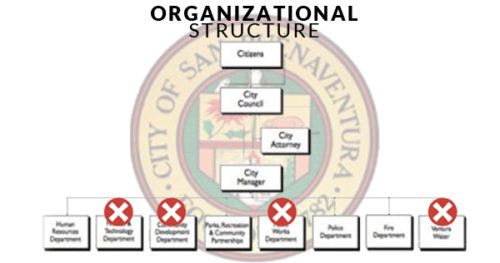

STOPPING THE BLEEDING

The need for key personnel is a huge problem. To fulfill any of our mayor’s goals requires adequate staff. The final 2019-2020 goal is to stabilize and strengthen our city government. The city has eight unfilled, critical managerial positions and dozens of vacant jobs. The city will achieve none of the other ambitious goals if there aren’t enough workers at City Hall.

The need for key personnel is a huge problem. To fulfill any of our mayor’s goals requires adequate staff. The final 2019-2020 goal is to stabilize and strengthen our city government. The city has eight unfilled, critical managerial positions and dozens of vacant jobs. The city will achieve none of the other ambitious goals if there aren’t enough workers at City Hall.

We know this is City Manager Alex McIntyre’s responsibility. In February, he requested six months to fill those positions. Four months remain. He needs time to recruit qualified people and offer competitive compensation. We hope Mr. McIntyre will fill those roles soon, but if he doesn’t, how will the City Council help and support him?

EDITORS’ COMMENTS

This year’s 2019 State-of-the-City speech was platitudes, a utopian vision and fuzzy logic. Those may have worked when we were a quaint beach town, but they don’t work today.

These are challenging times for the city. An understaffed government is trying to do the people’s work, but it’s hard. Issues like homelessness, economic development and community building, are secondary to the daily duties.

Mayor LaVere presented his vision of what Ventura could be. Unfortunately, he may have made promises his administration can’t keep. Worse still, his optimism lacked specifics and failed to address Ventura’s most pressing issues: employee retirement costs, water costs and public safety. Nonetheless, if the commitments are vague enough, no one will be able to measure if we keep them or not.

FORCE THE CITY COUNCIL TO BE MORE REALISTIC WITH ITS 2019 STATE-OF-THE-CITY GOALS

Below you’ll find the photos of our current City Council. Click on any Councilmember’s photo and you’ll open your email program ready to write directly to that Councilmember.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For more information like this, subscribe to our newsletter, Res Publica. Click here to enter your name and email address.

Costing over $500,000,000 is not the only issue. The more significant issue is that the City Council assumed DPR water was safe to drink.

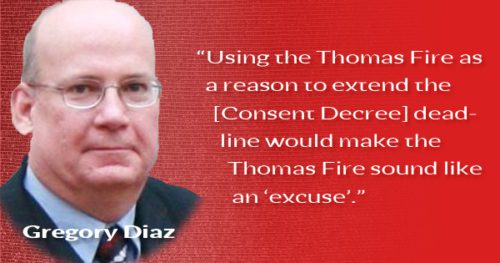

Costing over $500,000,000 is not the only issue. The more significant issue is that the City Council assumed DPR water was safe to drink.  However, the Consent Decree says the court can extend the time limit in the event of construction constraints, financing problems, or an emergency. It requires Ventura to petition the court requesting an extension, or an agreement with the plaintiff and their lawyers. That has not happened.

However, the Consent Decree says the court can extend the time limit in the event of construction constraints, financing problems, or an emergency. It requires Ventura to petition the court requesting an extension, or an agreement with the plaintiff and their lawyers. That has not happened. On February 4, 2019, Council Member Jim Friedman asked our City Attorney, Gregory Diaz about extending the deadline.

On February 4, 2019, Council Member Jim Friedman asked our City Attorney, Gregory Diaz about extending the deadline.

Ventura Water forces the City Council to get their information from the General Manager. Thus bypassing the entire reason the city established the Water Commission.

Ventura Water forces the City Council to get their information from the General Manager. Thus bypassing the entire reason the city established the Water Commission. You may not have heard about the incident. It’s not because Ventura Water didn’t announce it. They did. Ventura Water fulfilled the letter of the law, but it may have missed the intent behind it. Meeting the legal requirement seems to be the minimum standard. Yet setting the bar at the lowest level may place everyone’s health at risk in the future.

You may not have heard about the incident. It’s not because Ventura Water didn’t announce it. They did. Ventura Water fulfilled the letter of the law, but it may have missed the intent behind it. Meeting the legal requirement seems to be the minimum standard. Yet setting the bar at the lowest level may place everyone’s health at risk in the future. In July, Ventura Water withheld information from the Water Commission. A panel of experts examined

In July, Ventura Water withheld information from the Water Commission. A panel of experts examined

The City Council waffles on second-story height restrictions for

The City Council waffles on second-story height restrictions for  The City Council instructs Ventura Water to focus on connecting to State Water

The City Council instructs Ventura Water to focus on connecting to State Water

“I have never understood why it is ‘greed’ to want to keep the money you’ve earned, but not greed to want to take somebody else’s money.”

“I have never understood why it is ‘greed’ to want to keep the money you’ve earned, but not greed to want to take somebody else’s money.”

In March 2012, the Ventura City Council signed a Consent Decree that requires Ventura Water to stop putting 100% of its treated wastewater into the Santa Clara River estuary by January 2025. The decree stems from a Federal complaint filed by Wishtoya Foundation. Former City Manager, Rick Cole and Ventura Water General Manager, Shana Epstein, signed the consent decree on behalf of the city. The city no longer employs either of them.

In March 2012, the Ventura City Council signed a Consent Decree that requires Ventura Water to stop putting 100% of its treated wastewater into the Santa Clara River estuary by January 2025. The decree stems from a Federal complaint filed by Wishtoya Foundation. Former City Manager, Rick Cole and Ventura Water General Manager, Shana Epstein, signed the consent decree on behalf of the city. The city no longer employs either of them.

Mr. McIntyre is no stranger to managing municipalities so it goes without saying that he will become intricately familiar with Ventura’s budget and various legal agreements over the next few months. He begins his working relationship with a seven–member city council, two of which will be new and inexperienced. He also will meet a notoriously entrenched bureaucracy.

Mr. McIntyre is no stranger to managing municipalities so it goes without saying that he will become intricately familiar with Ventura’s budget and various legal agreements over the next few months. He begins his working relationship with a seven–member city council, two of which will be new and inexperienced. He also will meet a notoriously entrenched bureaucracy. Notwithstanding assurances from the Community Director, after the Thomas fire disaster,

Notwithstanding assurances from the Community Director, after the Thomas fire disaster,  The next priority will be the education and training needed to help the new city council become fully familiar with city budgets, the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), finances, the Casitas Water Agreement and various other legal agreements, protocols and procedures so future decisions will be based upon a good understanding of past city council actions.

The next priority will be the education and training needed to help the new city council become fully familiar with city budgets, the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), finances, the Casitas Water Agreement and various other legal agreements, protocols and procedures so future decisions will be based upon a good understanding of past city council actions. State experts have reported that Direct Potable Reuse (DPR) of wastewater is not safe for human consumption and further studies on the safe use of that water are not planned for another 3 years. Even if approved, the State of California will then have to develop and approve statewide standards. When and if that happens, this would be followed by a complex EIR and State Water Board hearing process to determine specific standards for Ventura.

State experts have reported that Direct Potable Reuse (DPR) of wastewater is not safe for human consumption and further studies on the safe use of that water are not planned for another 3 years. Even if approved, the State of California will then have to develop and approve statewide standards. When and if that happens, this would be followed by a complex EIR and State Water Board hearing process to determine specific standards for Ventura.

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

The new City Council can take three steps to address water. First, they must request a modification to

The new City Council can take three steps to address water. First, they must request a modification to Housing Ventura’s homeless was a high priority. Some thought affordable housing was the solution. Others mentioned the homeless shelter. Some interviewees distinguished between the mentally ill living on the streets and the vagrants. Each saw it as a countywide problem with Ventura as its nexus. The county jail and the psychiatric hospital are in Ventura, making the city a natural final destination for the homeless to stay. One interviewee described it as a “catch and release” program by the other cities into Ventura.

Housing Ventura’s homeless was a high priority. Some thought affordable housing was the solution. Others mentioned the homeless shelter. Some interviewees distinguished between the mentally ill living on the streets and the vagrants. Each saw it as a countywide problem with Ventura as its nexus. The county jail and the psychiatric hospital are in Ventura, making the city a natural final destination for the homeless to stay. One interviewee described it as a “catch and release” program by the other cities into Ventura. The new Council needs to apply critical thinking and be willing to question all city staff reports and recommendations. To do so requires financial literacy. Each Councilmember must study the city budget and Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR).

The new Council needs to apply critical thinking and be willing to question all city staff reports and recommendations. To do so requires financial literacy. Each Councilmember must study the city budget and Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR). Many complex issues face Ventura. All City Council candidates need to be aware of the problems and have a plan to address them. We can’t rely on the candidates alone to be knowledgeable. It’s each person’s responsibility to be aware of the challenges before us. It’s equally important that each voter be confident that the candidates understand them. Only then do our elected officials represent us

Many complex issues face Ventura. All City Council candidates need to be aware of the problems and have a plan to address them. We can’t rely on the candidates alone to be knowledgeable. It’s each person’s responsibility to be aware of the challenges before us. It’s equally important that each voter be confident that the candidates understand them. Only then do our elected officials represent us

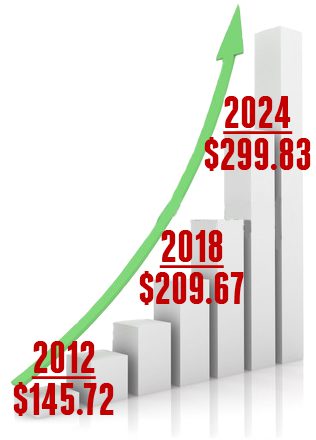

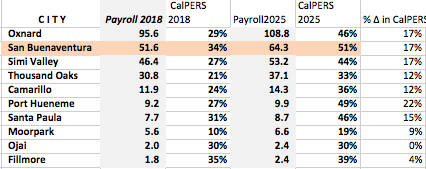

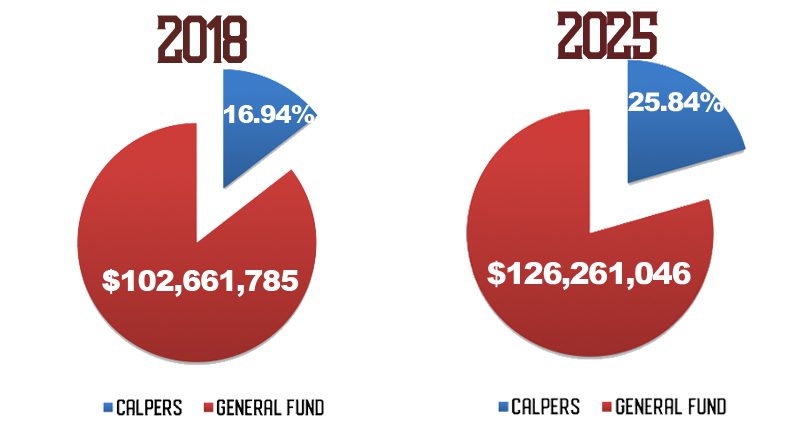

Ventura is already paying 34 cents to CalPERS for every dollar it pays its active employees. In six years, that amount will go up to an unsustainable 51 cents for every dollar of payroll—more than any city in Ventura County. Pensions are already crowding out other essential city services like filling potholes, fixing infrastructure and even hiring more police officers and firefighters.

Ventura is already paying 34 cents to CalPERS for every dollar it pays its active employees. In six years, that amount will go up to an unsustainable 51 cents for every dollar of payroll—more than any city in Ventura County. Pensions are already crowding out other essential city services like filling potholes, fixing infrastructure and even hiring more police officers and firefighters.

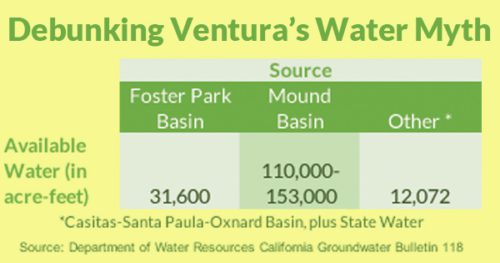

Ventura needs to get its priorities straight about water—and fast. On July 9th, Ventura Water will ask the City Council to approve direct potable reuse (DPR). Ventura Water views DRP as a primary alternative source for increased drinking water. The project will cost $538 million of taxpayer dollars. The trouble is, it’s an untested, unproven and unregulated solution to our water needs. Why would the City Council gamble with the health of its citizens?

Ventura needs to get its priorities straight about water—and fast. On July 9th, Ventura Water will ask the City Council to approve direct potable reuse (DPR). Ventura Water views DRP as a primary alternative source for increased drinking water. The project will cost $538 million of taxpayer dollars. The trouble is, it’s an untested, unproven and unregulated solution to our water needs. Why would the City Council gamble with the health of its citizens? Two legal agreements jeopardize Ventura’s water supply. The first was a Consent Decree requiring Ventura to cease putting 100% of its treated wastewater into the Santa Clara River estuary. It needs to be diverted somewhere else by January 2025.

Two legal agreements jeopardize Ventura’s water supply. The first was a Consent Decree requiring Ventura to cease putting 100% of its treated wastewater into the Santa Clara River estuary. It needs to be diverted somewhere else by January 2025. The new Casitas Water contract entitles Ventura an amount of water based on projected needs and adjusted for drought staging conditions. Ventura Water anticipates our water needs at 5,669 acre-feet per year by 2025. By then, they expect we’ll be out of our current drought conditions. Under the1995 contract, Ventura was allowed a minimum of 6,000 acre-feet of water per year. That water could be used in the western part of Ventura (everything west of Mills Road) and the eastern part of the city, if necessary. The new contract changes that and puts East Ventura at a disadvantage. The old agreement allowed Ventura to blend Casitas water with the East End to achieve better quality.

The new Casitas Water contract entitles Ventura an amount of water based on projected needs and adjusted for drought staging conditions. Ventura Water anticipates our water needs at 5,669 acre-feet per year by 2025. By then, they expect we’ll be out of our current drought conditions. Under the1995 contract, Ventura was allowed a minimum of 6,000 acre-feet of water per year. That water could be used in the western part of Ventura (everything west of Mills Road) and the eastern part of the city, if necessary. The new contract changes that and puts East Ventura at a disadvantage. The old agreement allowed Ventura to blend Casitas water with the East End to achieve better quality.  In August 2016, a report by a state-appointed panel of experts concluded it was “technically” feasible to use DPR, but there are serious health risks. Here are some fundamental problems outlined:

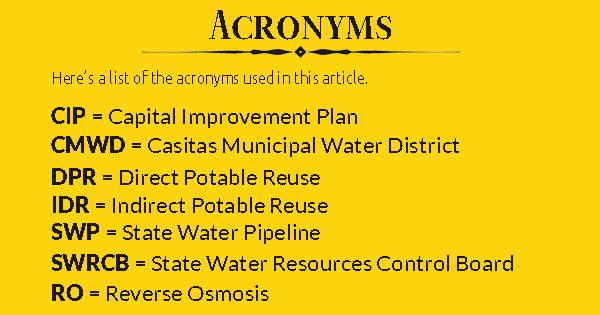

In August 2016, a report by a state-appointed panel of experts concluded it was “technically” feasible to use DPR, but there are serious health risks. Here are some fundamental problems outlined: The cost of DPR wastewater is high. According to the Capital Improvement Plan (CIP), the wastewater and water costs will total approximately $538 million once financing costs are added. Included in those costs are advanced purification facilities to treat the wastewater that will cost $77.7 million. Also included is another $170 million to pump the water north to the desalination/Reverse Osmosis plant. Other infrastructure improvements comprise the remaining costs—including a brine line to carry away contaminants from the new RO plant.

The cost of DPR wastewater is high. According to the Capital Improvement Plan (CIP), the wastewater and water costs will total approximately $538 million once financing costs are added. Included in those costs are advanced purification facilities to treat the wastewater that will cost $77.7 million. Also included is another $170 million to pump the water north to the desalination/Reverse Osmosis plant. Other infrastructure improvements comprise the remaining costs—including a brine line to carry away contaminants from the new RO plant.